AURORAS AS TIME MACHINES: The

fall of 1770 was not a good time for Capt. James Cook and the

crew of the HMS Endeavour. One year earlier, they successfully

observed the transit of Venus from Tahiti. Many aboard would rue

leaving that paradise. After a violent stop in New Zealand, Endeavour

struck Australia's Great Barrier Reef, tearing a massive hole in

her hull and beaching the vessel for 7 weeks for repairs. By the

time the ship was underway again, many of the crew were suffering

from tropical diseases, malnutrition, and exhaustion.

That's when the geomagnetic storm struck.

Endeavour was sailing near Timor Island (latitude -9.9o) on Sept. 16, 1770, when red auroras appeared in the night sky. The expedition's naturalist Joseph A. Banks and his assistant Sydney Parkinson both noted the event in their logs, although they were unsure what they had seen. The idea that auroras could spread to within 10 degrees of the equator seemed outlandish.

Yet auroras they were. A 2017 study led by Hisashi Hayakawa established that Cook's auroras were part of an extreme 9-day display across China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Some of the lights were "as bright as a full Moon."

Clearly, the "Cook Event" was a big deal. But how big? Researchers have long wondered. Magnetometers were only invented in the 19th century, so there are no scientific measurements of geomagnetic activity before then. Rating old storms has been a matter of guesswork.

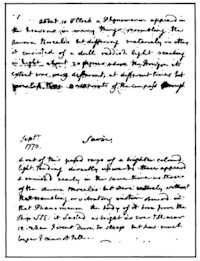

Right: Joseph Banks' 1770 aurora log entry.

Right: Joseph Banks' 1770 aurora log entry.

A study published in the April 2025 edition of Space Weather may have solved this problem by turning auroras into time machines.

In their paper,

Jeffrey Love of the US Geological Survey and colleagues analyzed 54

geomagnetic storms from 1859 to 2005, using both magnetometer data and

overhead aurora sightings. By correlating the two, they developed a

statistical model that lets researchers estimate the strength of

historical storms based on eyewitness accounts—no magnetometer required.

One of the key findings of their study is that Cook's storm was (within the margin of error) the same size as the famous Carrington Event of 1859. They also found a very big storm just a few days before the Carrington Event. On August 28, 1859, there were no magnetometer data available because it was Sunday, a day off for observatory staff. However, auroras were reported overhead in Havana, Cuba. Love's model pegged that storm at ~two-thirds of the Carrington Event, making it one of the biggest geomagnetic storms on record.

The good news for Cook and his crew: They weren't using modern technology like radio or GPS, which might have failed. Cook had no trouble navigating the magnetic storm. If it happened again today, we might not be so lucky.

Read the original research here.

No comments:

Post a Comment