It was in September 1974 in NW Iowa and north we had a black frost. Killed every thing. Think around Sept third. Fifty years ago.

THIS is where I hide the best stuff... and hey... there are lots of posts so go search the BLOG ARCHIVE - (͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

It was in September 1974 in NW Iowa and north we had a black frost. Killed every thing. Think around Sept third. Fifty years ago.

The Japanese word “hikikomori” translates to “pulling inwards”. The term was coined in 1998 by Japanese psychiatrist Professor Tamaki Saito to describe a burgeoning social phenomenon among young people who, feeling the extreme pressures to succeed in their school, work and social lives and fearing failure, decided to withdraw from society. At the time, it was estimated that around a million people were choosing to not leave their homes or interact with others for at least six months, some for years. It is now estimated that around 1.2% of Japan’s population are hikikomori.

When this trend was identified in the mid-90s, it was used to describe young, male recluses. However, research has shown that there is an increasing number of middle-aged hikikomori. In addition, many female hikikomori are not acknowledged because women are expected to adopt domestic roles and their withdrawal from society can go unnoticed.

Japanese manga researchers Ulrich Heinze and Penelope Thomas explain that, in recent years, there has been a subtle change in how people understand the phenomena of hikikomori. This shift is manifested through increased awareness of the complexity of the hikikomori experience within the mainstream media and acknowledgement of social pressures that can lead to social withdrawal. They suggest that the refusal to conform to social “norms” (such as career progression, marriage and parenthood) can be understood as a radical act of introversion and self-discovery.

In line with this image change, some hikikomori have rich creative lives and this can sustain vital human connection. Many people are now living in compulsory isolation because of COVID-19. While this is not the same as being hikikomori, we can learn from the different different ways in which these people have navigated through, or are still navigating through, experiences of isolation.

Ex-hikikomori artist Atsushi Watanabe explains that his three-year isolation began through “multiple stages of withdrawal from human relationships, which resulted in feeling completely isolated”. At one point, he remained in bed for over seven months. It wasn’t until he began to see the negative impact that his withdrawal was having on his mother, that he was able to leave his room and reconnect with the world.

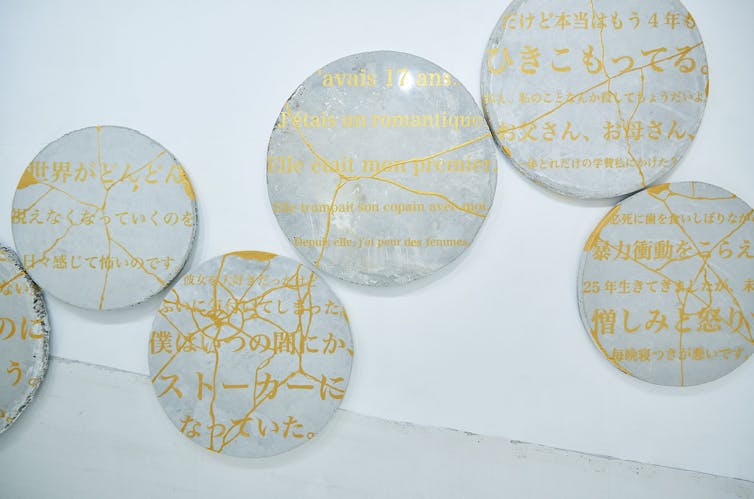

Tell me your emotional scars is an ongoing creative project by Watanabe. In this project, people can submit anonymous messages on a website, sharing experiences of emotional pain. Watanabe renders the messages into concrete plates, which he then breaks and puts back together again using the traditional Japanese art of kintsugi.

Kinstugi involves the joining of broken ceramics using a lacquer mixed with powdered gold. It is also a philosophy that stresses the art of resilience. The breakage is not the end of the object or something to be hidden, but a thing to be celebrated as part of the object’s history.

Tell me your emotional scars can be understood as a sublimation of this emotional pain – conveying negative, asocial feelings through a process that is socially acceptable, positive and beautiful. These works are a testament to suffering, but one that celebrates the possibility of healing and transformation.

For Watanabe, becoming hikikomori is often a manifestation of emotional scars, and he wants to create alternative ways of understanding unresolved past experiences. Watanabe asks us to “listen to the shaky voices that cannot usually be heard”. Listening to, and sharing experiences of hardship and even pain is one way to address the rise in loneliness that has resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Artist Nito Souji became a hikikomori because he wanted to spend his time doing “only things that are worthwhile”. Souji has spent ten years in isolation developing his creative practice, leading to a video game that explores the hikikomori experience.

The trailer for the video game Pull Stay opens with a scene in which three people break into the home of a hikikomori. The player must fights off intruders as the hikikomori’s robot alter-ego by, for example, frying them in tempura batter or firing water melons at them.

The aim of Pull Stay is to protect the home and seclusion of the hikikomori character. In doing so, the player begins to embody a visceral need for privacy. Pull Stay is testament to the creative outcomes that can come from carving out a profound sense of “headspace”. Souji explains his creative process as, “having hope and making a little progress every day. That worked for me”.

Despite choosing to withdraw from society, sustaining hope and indirect connection through creative practice has helped artists such as Souji use this time for self-development. His aim is, and always has been, to be able to reenter society, but on his own terms.

Well-known Japanese entrepreneur Kazumi Ieiri, himself a recovered recluse, describes the hikikomori experience as “a situation where the knot is untied between you and society”. But he continues, there is no need to hurry to retie social bonds, rather to “tie small knots, little by little”.

The process of returning to “normal life” might be gradual for many of us, but creative expression could be a powerful way of to both share experiences of isolation and to reconnect with others within and beyond lockdown.

Lecturer in Visual Communication, Solent University

Jessica Holtaway does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

👇

sign up: https://thenaturalhistorymuseum.org/video-highlights-resisting-the-global-land-grab/

From the brilliant Charles Hugh Smith: https://charleshughsmith.blogspot.com/2024/07/how-those-using-useful-idiots-become.html

And that's how totalitarian movements come to power: the citizens

give up on the Establishment factions, as they've failed to solve the

problems being exploited by extremist groups.

Useful Idiots describes those who support or encourage

movements of mayhem in the misguided belief that these movements are

positive or necessary. The classic example (and no, V. Lenin did not

coin the phrase) are Western fellow-travelers who supported the

totalitarian Soviet regime out of naivete, idealism or sentimentality.

But there is another class of Useful Idiots: when powerful

factions are jockeying for supremacy in societies riven by chronic

crisis (economic stagnation, social discord, etc.), some of these groups

may cynically see extremist movements as Useful Idiots who can be directed to further the interests of the cynical group.

March 13, 2021: They call it “the day the sun brought darkness.” On March 13, 1989, a powerful coronal mass ejection (CME) hit Earth’s magnetic field. Ninety seconds later, the Hydro-Québec power grid failed. During the 9 hour blackout that followed, millions of Quebecois found themselves with no light or heat, wondering what was going on?

“It was the biggest geomagnetic storm of the Space Age,” says Dr. David Boteler, head of the Space Weather Group at Natural Resources Canada. “March 1989 has become the archetypal disturbance for understanding how solar activity can cause blackouts.”

It seems hard to believe now, but in 1989 few people realized solar storms could bring down power grids. The warning bells had been ringing for more than a century, though. In Sept. 1859, a similar CME hit Earth’s magnetic field–the infamous “Carrington Event“–sparking a storm twice as strong as March 1989. Electrical currents surged through Victorian-era telegraph wires, in some cases causing sparks and setting telegraph offices on fire. These were the same kind of currents that would bring down Hydro-Québec.

“The March 1989 blackout was a wake-up call for our industry,” says Dr. Emanuel Bernabeu of PJM, a regional utility that coordinates the flow of electricity in 13 US states. “Now we take geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) very seriously.”

What are GICs? Freshman physics 101: When a magnetic field swings back and forth, electricity flows through conductors in the area. It’s called “magnetic induction.” Geomagnetic storms do this to Earth itself. The rock and soil of our planet can conduct electricity. So when a CME rattles Earth’s magnetic field, currents flow through the soil beneath our feet.

Québec is especially vulnerable. The province sits on an expanse of Precambrian igneous rock that does a poor job conducting electricity. When the March 13th CME arrived, storm currents found a more attractive path in the high-voltage transmission lines of Hydro-Québec. Unusual frequencies (harmonics) began to flow through the lines, transformers overheated and circuit breakers tripped.

After darkness engulfed Quebec, bright auroras spread as far south as Florida, Texas, and Cuba. Reportedly, some onlookers thought they were witnessing a nuclear exchange. Others thought it had something to do with the space shuttle (STS-29), which remarkably launched on the same day. The astronauts were okay, although the shuttle did experience a mysterious problem with a fuel cell sensor that threatened to cut the mission short. NASA has never officially linked the sensor anomaly to the solar storm.

Much is still unknown about the March 1989 event. It occurred long before modern satellites were monitoring the sun 24/7. To piece together what happened, Boteler has sifted through old records of radio emissions, magnetograms, and other 80s-era data sources. He recently published a paper in the research journal Space Weather summarizing his findings — including a surprise:

“There were not one, but two CMEs,” he says.

The sunspot that hurled the CMEs toward Earth, region 5395, was one of the most active sunspot groups ever observed. In the days around the Quebec blackout it produced more than a dozen M- and X-class solar flares. Two of the explosions (an X4.5 on March 10th and an M7.3 on March 12th) targeted Earth with CMEs.

“The first CME cleared a path for the second CME, allowing it to strike with unusual force,” says Boteler. “The lights in Québec went out just minutes after it arrived.”

Among space weather researchers, there has been a dawning awareness in recent years that great geomagnetic storms such as the Carrington Event of 1859 and The Great Railroad Storm of May 1921 are associated with double (or multiple) CMEs, one clearing the path for another. Boteler’s detective work shows that this is the case for March 1989 as well.

The March 1989 event kicked off a flurry of conferences and engineering studies designed to fortify grids. Emanuel Bernabeu’s job at PJM is largely a result of that “Québec epiphany.” He works to protect power grids from space weather — and he has some good news.

“We have made lots of progress,” he says. “In fact, if the 1989 storm happened again today, I believe Québec would not lose power. The modern grid is designed to withstand an extreme 1-in-100 year geomagnetic event. To put that in perspective, March 1989 was only a 1-in-40 or 50 year event–well within our design specs.”

Some of the improvements have come about by hardening equipment. For instance, Bernabeu says, “Utilities have upgraded their protection and control devices making them immune to type of harmonics that brought down Hydro-Québec. Some utilities have also installed series capacitor compensation, which blocks the flow of GICs.”

Other improvements involve operational awareness. “We receive NOAA’s space weather forecast in our control room, so we know when a storm is coming,” he says. “For severe storms, we declare ‘conservative operations.’ In a nutshell, this is a way for us to posture the system to better handle the effects of geomagnetic activity. For instance, operators can limit large power transfers across critical corridors, cancel outages of critical equipment and so on.”

The next Québec-level storm is just a matter of time. In fact, we could be overdue. But, if Bernabeu is correct, the sun won’t bring darkness, only light.

CME IMPACT: A CME struck Earth today, July 25th, at 1422 UT. We're not sure, but this could be the halo CME launched toward Earth by a dark plasma eruption on July 21st. G1-class geomagnetic storms are possible in the hours ahead as Earth moves through the CME's magnetized wake. CME impact alerts: SMS Text

MAJOR FARSIDE SOLAR FLARE: The biggest flare of Solar Cycle 25 just exploded from the farside of the sun. X-ray detectors on Europe's Solar Orbiter (SolO) spacecraft registered an X14 category blast:

Solar Orbiter was over the farside of the sun when the explosion occured on July 23rd, in perfect position to observe a flare otherwise invisible from Earth.

"From the estimated GOES class, it was the largest flare so far," says Samuel Krucker of UC Berkeley. Krucker is the principal investigator for STIX, an X-ray telescope on SolO which can detect solar flares and classify them on the same scale as NOAA's GOES satellites. "Other large flares we've detected are from May 20, 2024 (X12) and July 17, 2023 (X10). All of these have come from the back side of the sun."

Meanwhile on the Earthside of the sun, the largest flare so far registered X8.9 on May 14, 2024. SolO has detected at least three larger farside explosions, which means our planet has been dodging a lot of bullets.

The X14 farside flare was indeed a major event. It hurled a massive CME into space, shown here in a coronagraph movie from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO):

The CME sprayed energetic particles all over the solar system. Earth itself was hit by 'hard' protons (E > 100 MeV) despite being on the opposite side of the sun.

"This is a big one--a 360 degree event," says George Ho of the Southwest Research Institute, principal investigator for one of the energetic particle detectors onboard SolO. "It also caused a high dosage at Mars."

SolO was squarely in the crosshairs of the CME, and on July 24th it experienced a direct hit. In a matter of minutes, particle counts jumped almost a thousand-fold as the spacecraft was peppered by a hail storm energetic ions and electrons.

"This is something we call an 'Energetic Storm Particle' (ESP) event," explains Ho. "It's when particles are locally accelerated in the CME's shock front [to energies higher than a typical solar radiation storm]. An ESP event around Earth in March 1989 caused the Great Quebec Blackout."

So that's what might have happened if the CME hit Earth instead of SolO. Maybe next time. The source of this blast will rotate around to face our planet a week to 10 days from now, so stay tuned. Solar flare alerts: SMS Text