Tutu Hockey

THIS is where I hide the best stuff... and hey... there are lots of posts so go search the BLOG ARCHIVE - (͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)

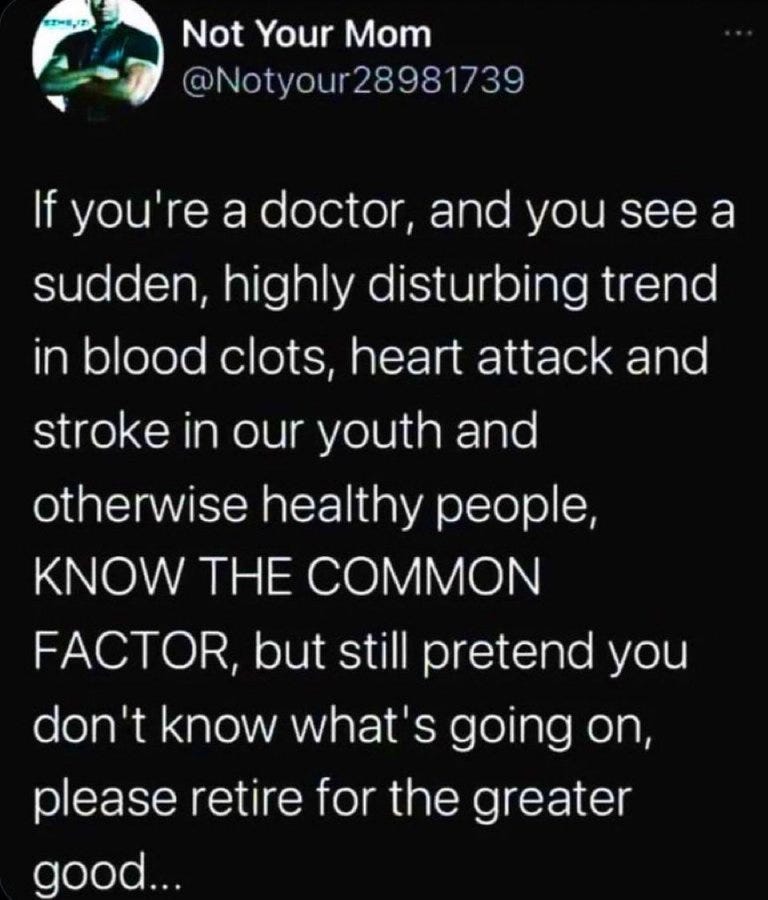

their plan continues

👇

https://x.com/theHFDF/status/2008609872603152518?s=20 Holy shit. Health Freedom Defense Fund on X: "A federal court quietly ruled that the government can force ANY medical intervention on you—with no evidence or judicial review. Almost no one noticed. The Ninth Circuit said as long as officials say “public health,” courts shouldn’t question them. But we just fought back. https://t.co/FAMZlgD5mU" / X

- The Alchemist's Dream

Read on Substackmilitary grade weapon?

👇 Just when you thought you'd heard it all, this resurfaced interview with Professor Francis Boyle—the man who literally WROTE the Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act of 1989—will leave you speechless. Just days after Professor Francis Boyle agreed to testify against Bill Gates and Albert Bourla regarding the deadly mRNA COVID vaccines... He was FOUND DEAD. Boyle authored the “Bioweapons Act” in the US and called mRNA injections ‘Bioweapons & Franken-Shots’. Where does the Pentagon fit into all this?... He officially states that both SARS-CoV-2 and mRNA injections were offensive biological weapons programs funded by DARPA from the beginning. Gain of function? That was the cover story. According to Boyle, the real goal has always been population reduction technology “with lethal vaccines.” He goes further—he defines the rules as “synthetic biological weapons of mass destruction” because they trigger prion-like autoimmune reactions and turbo tumors. Boyle filed lawsuits, pleaded with Congress, and warned the world. Just 20 days after agreeing to testify for the prosecution, he was found dead. The same pattern we've seen with dozens of doctors and whistleblowers since 2020. The most chilling part? Boyle predicted exactly what we are seeing now: myocarditis, strokes, infertility, and tumors exploding in the injected systems. He said the spike protein itself is the weapon and that the lipid nanoparticles were engineered to cross the blood-brain barrier. It was not a mistake. It was a military-grade killing agent disguised as “public health.”

- Dr. David Cartland

Read on Substack

oh yeah...

Trace's book

-

Dean Henderson and Jeff discuss current events and take a whack at the global oligarchy. Check out more info from Jeff Rense at Alt News ...

-

Burt Bacharach, Music artist Co-author (with lyricist Hal David) of an extensive string of hits in the '60s, Burt Bacharach is one of...

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)